| Aircraft |

| |

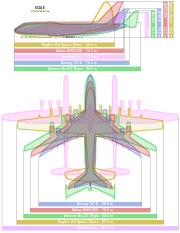

| An Airbus A380, the world's largest passenger airliner |

An aircraft is a vehicle which is able to fly through the Earth's atmosphere or through any other atmosphere. Most rocket vehicles are not aircraft because they are not supported by the surrounding air. All the human activity which surrounds aircraft is called aviation.

Manned aircraft are flown by a pilot. Until the 1960s, unmanned aircraft were called drones. During the 1960s, the U.S. military brought the term remotely piloted vehicle (RPV) into use. More recently the term unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) has become common.

Kinds of aircraft

Aircraft fall into two categories: lighter-than-air (aerostats), and heavier-than-air (aerodynes).

[edit] Lighter than air—aerostats

Aerostats use buoyancy to float in the air in much the same way that ships float on the water. They are characterized by one or more large gasbags or canopies, filled with a relatively low density gas such as helium, hydrogen or hot air, which is less dense than the surrounding air. When the weight of this is added to the weight of the aircraft structure, it adds up to the same weight as the air that the craft displaces.

Small hot air balloons called sky lanterns date back to the 3rd century BC and were only the second type of aircraft to fly, the first being kites.

Originally a "balloon" was any aerostat, while the term "airship" was used for large powered aircraft designs—usually fixed-wing—though none had yet been built. The advent of powered balloons, called dirigible balloons, and later of rigid hulls allowing a great increase in size, began to change the way these words were used. Huge powered aerostats, characterized by a rigid outer framework and separate aerodynamic skin surrounding the gas bags, were produced, the Zeppelins being the largest and most famous. There were still no aeroplanes or non-rigid balloons large enough to be called airships, so "airship" came to be synonymous with these monsters. Then several accidents, such as the Hindenburg disaster in 1937, led to the demise of these airships. Nowadays a balloon is an unpowered aerostat, whilst an airship is a powered one.

A powered, steerable aerostat is called a dirigible. Sometimes this term is applied only to non-rigid balloons, and sometimes dirigible balloon is regarded as the definition of an airship (which may then be rigid or non-rigid). Non-rigid dirigibles are characterized by a moderately aerodynamic gasbag with stabilizing fins at the back. These soon became known as blimps. During the Second World War, this shape was widely adopted for tethered balloons; in windy weather this both reduces the strain on the tether and stabilizes the balloon. The nickname blimp was adopted along with the shape. In modern times any small dirigible or airship is called a blimp, though a blimp may be unpowered as well as powered.

Heavier than air—aerodynes

Heavier-than-air aircraft must find some way to push air or gas downwards, so that a reaction occurs (by Newton's laws of motion) to push the aircraft upwards. This dynamic movement through the air is the origin of the term aerodyne. There are two ways to produce dynamic upthrust: aerodynamic lift, and powered lift in the form of engine thrust.

Aerodynamic lift is the most common, with aeroplanes being kept in the air by the forward movement of wings, and rotorcraft by spinning wing-shaped rotors sometimes called rotary wings. A wing is a flat, horizontal surface, usually shaped in cross-section as an aerofoil. To fly, the wing must move forwards through the air; this movement of air over the aerofoil shape deflects air downward to create an equal and opposite upward force, called lift, according to Newton's third law of motion. A flexible wing is a wing made of fabric or thin sheet material, often stretched over a rigid frame. A kite is tethered to the ground and relies on the speed of the wind over its wings, which may be flexible or rigid, fixed or rotary.

With powered lift, the aircraft directs its engine thrust vertically downwards.

The initialism VTOL (vertical take off and landing) is applied to aircraft that can take off and land vertically. Most are rotorcraft. Others, such as the Hawker Siddeley Harrier, take off and land vertically using powered lift and transfer to aerodynamic lift in steady flight. Similarly, STOL stands for short take off and landing. Some VTOL aircraft often operate in a short take off/vertical landing regime known as STOVL.

A pure rocket is not usually regarded as an aerodyne, because it does not depend on the air for its lift (and can even fly into space), however many aerodynamic lift vehicles have been powered or assisted by rocket motors. Rocket-powered missiles which obtain aerodynamic lift at very high speed due to airflow over their bodies, are a marginal case.

Fixed-wing aircraft

Aeroplanes or airplanes are technically called fixed-wing aircraft.

The forerunner of the aeroplane is the kite. Whereas an aeroplane relies on its forward speed to create airflow over the wings, a kite is tethered to the ground and relies on the wind blowing over its wings to provide lift. Kites were the first kind of aircraft to fly, and were invented in China around 500 BC. Much aerodynamic research was done with kites before test aircraft, wind tunnels and computer modelling programs became available.

The first heavier-than-air craft capable of controlled free flight were unpowered aeroplanes or gliders. A glider designed by Cayley carried out the first true manned, controlled flight in 1853.

Besides the method of propulsion, aeroplanes are generally characterized by their wing configuration. The most important wing characteristics are:

- Number of planes - Monoplane, biplane, etc.

- Wing support - Braced or cantilever, rigid or flexible.

- Wing planform - including aspect ratio, angle of sweep and any variations along the span. Includes the important class of delta wings.

- Location of the horizontal stabiliser, if any.

- Dihedral angle - positive, zero or negative (anhedral).

A variable geometry aircraft can change its wing configuration during flight.

A flying wing has no fuselage, though it may have small blisters or pods. The opposite of this is a lifting body which has no wings, though it may have small stabilising and control surfaces.

Seaplane: Be-8 was built in 1947

Seaplanes and Floatplanes differ in that a seaplane has the bottom of its fuselage shaped hydrodynamically and it sits directly on the water when at rest, while a floatplane has two or more floats attached below the rest of the aircraft so that the fuselage remains clear of the water at all times.

Some people consider wing-in-ground-effect vehicles to be aeroplanes, others do not. These craft "fly" close to the surface of the ground or water. An example is the Russian ekranoplan also nicknamed the "Caspian Sea Monster". Man-powered aircraft also rely on ground effect to remain airborne, but this is only because they are so underpowered - the airframe is theoretically capable of flying much higher. (Hovercraft are not considered to be aircraft, since they rely wholly on the pressure of air on the ground beneath, and have no aerodynamic lifting surface).

Rotorcraft

Rotorcraft, or rotary-wing aircraft, use a spinning rotor with aerofoil section blades (a rotary wing) to provide lift. Types include helicopters, autogyros and various hybrids such as gyrodynes and compound rotorcraft.

Helicopters have powered rotors. The rotor is driven (directly or indirectly) by an engine and pushes air downwards to create lift. By tilting the rotor forwards, the downwards flow is tilted backwards, producing thrust for forward flight.

Autogyros or gyroplanes have unpowered rotors, with a separate power plant to provide thrust. The rotor is tilted backwards. As the autogyro moves forward, air blows upwards through it, making it spin.(cf. Autorotation)

US-Recognition Manual (very likely copy of german drawing)

This spinning dramatically increases the speed of airflow over the rotor, to provide lift. Juan de la Cierva (a Spanish civil engineer) used the product name autogiro, and Bensen used gyrocopter. Rotor kites, such as the Focke Achgelis Fa 330 are unpowered autogyros, which must be towed by a tether to give them forward ground speed or else be tether-anchored to a static anchor in a high-wind situation for kited flight.

Gyrodynes are a form of helicopter, where forward thrust is obtained from a separate propulsion device rather than from tilting the rotor. The definition of a 'gyrodyne' has changed over the years, sometimes including equivalent autogyro designs. The most important characteristic is that in forward flight air does not flow significantly either up or down through the rotor disc but primarily across it. The Heliplane is a similar idea.

Compound rotorcraft have wings which provide some or all of the lift in forward flight. Compound helicopters and compound autogyros have been built, and some forms of gyroplane may be referred to as compound gyroplanes. Tiltrotor aircraft (such as the V-22 Osprey) have their rotors horizontal for vertical flight, and pivot the rotors vertically like a propeller for forward flight. The Coleopter had a cylindrical wing forming a duct around the rotor. On the ground it sat on its tail, and took off and landed vertically like a helicopter. The whole aircraft would then have tilted forward to fly as a propeller-driven aeroplane using the duct as a wing (though this transition was never achieved in practice.)

Some rotorcraft have reaction-powered rotors with gas jets at the tips, but most have one or more lift rotors powered from engine-driven shafts.

[edit] Other methods of lift

X24B lifting body, specialized glider

- A lifting body is the opposite of a flying wing. In this configuration the aircraft body is shaped to produce lift. If there are any wings, they are too small to provide all the lift. Lifting bodies are not efficient: the aircraft must travel at high speed to generate enough lift to fly. The most famous lifting body design is the Space Shuttle, while some supersonic missiles obtain lift from the airflow over a tubular body.

- Powered lifts rely entirely on engine thrust to hold them up in the air. There are few practical applications. Experimental designs have been built for personal fan-lift hover platforms and jetpacks or for VTOL research (for example the flying bedstead). VTOL jet aircraft such as the Harrier jump-jet take off and land vertically in powered-lift configuration, then transition to conventional configuration for forward flight.

- The FanWing is a recent innovation and represents a completely new class of aircraft. This uses a fixed wing with a cylindrical fan mounted spanwise just above. As the fan spins, it creates an airflow backwards over the upper surface of the wing, creating lift. The fan wing is (2005) in development in the United Kingdom.

[edit] Propulsion

[edit] Unpowered

Some types of aircraft, such as balloons, kites and gliders, do not have any propulsion.

Balloons drift with the wind, though normally the pilot can control the altitude either by heating the air or by releasing ballast, giving some directional control (since the wind direction changes with altitude). A wing-shaped hybrid balloon can glide directionally when rising or falling; but a spherically-shaped balloon does not have such directional control.Flying with Gravity

Kites are tethered to the ground or other object (fixed or mobile) or other means that maintains tension in the kite line; and rely on virtual or real wind blowing over and under them to generate lift and drag. Kytoons are balloon kites that are shaped and tethered to obtain kiting deflections, and can be lighter-than-air, neutrally buoyant, or heavier-than air.

Gliders gain their initial flying speed from some launch mechanism, and then gain additional energy from gravity and from updrafts such as thermal currents. Takeoff may be by launching forwards and downwards from a high location, or by pulling into the air on a towline, by a ground-based winch or vehicle, or by a powered "tug" aircraft. For a glider to maintain its forward air speed and lift, it must descend in relation to the air (but not necessarily in relation to the ground). The first practical, controllable example was designed and built by the British scientist and pioneer George Cayley who is universally recognised as the first aeronautical engineer.

[edit] Propellers

A propeller comprises a set of small, wing-like aerofoils set around a central hub which spins on an axis aligned in the direction of travel. Spinning the propeller creates aerodynamic lift, or thrust, in a forward direction. A contra-prop arrangement has a second propeller close behind the first one on the same axis, which rotates in the opposite direction.

A variation on the propeller is to use many broad blades to create a fan. Such fans are traditionally surrounded by a ring-shaped fairing or duct, as ducted fans. Some experimental designs do not use a duct, and are sometimes called propfans. How to tell whether it's a propellor or a fan? Look at it from the front when stationary: if you can see in between the blades then it is a propellor, while if the blades pretty much block the view it is a fan.

During the 1940's and again following the 1973 energy crisis, development work was done on propellers and propfans with swept tips or curved "scimitar-shaped" blades for use in high-speed applications, to delay the onset of shockwaves where the blade tips approach the speed of sound in similar manner to wing sweepback.

Many kinds of power plant have been used to drive propellers.

The earliest designs used man power to give dirigible balloons some degree of control, and go back to Jean-Pierre Blanchard in 1784. Attempts to achieve heavier-than-air manpowered flight did not succeed until Paul MacCready's Gossamer Condor in 1977.

The first powered flight was made in a steam-powered dirigible by Henri Giffard in 1852. Attempts to marry a practical lightweight steam engine to a practical fixed-wing airframe did not succeed until much later, by which time the internal combustion engine was already dominant.

From the first powered aeroplane flight by the Wright brothers until World War II, propellers turned by the internal combustion piston engine were virtually the only type of propulsion system in use. (See also: Aircraft engine.) The piston engine is still used in the majority of smaller aircraft produced, since it is efficient at the lower altitudes and slower speeds suited to propellers.

Turbine engines need not be used as jets (see below), but may be geared to drive a propeller in the form of a turboprop. Modern helicopters also typically use turbine engines to power the rotor. Turbines provide more power for less weight than piston engines, and are better suited to small-to-medium size aircraft or larger, slow-flying types.

Other less common power sources include:

- Electric motors, often linked to solar panels to create a solar-powered aircraft.

- Rubber bands, wound many times to store energy, are mostly used for flying models.

[edit] Jet engines

-

Jet engines provide thrust by taking in air, burning it with fuel, and accelerating the exhaust rearwards so that it ejects at high speed. The reaction against this acceleration provides the engine thrust.

Jet engines can provide much higher thrust than propellers, and are naturally efficient at higher altitudes, being able to operate above 40,000 ft (12,000 m). They are also much more fuel-efficient than rockets. Consequently, nearly all high-speed and high-altitude aircraft use jet engines.

The early turbojet and modern turbofan use a spinning turbine to create airflow for takeoff and to provide thrust. Many, mostly in military aviation, use afterburners which inject extra fuel into the exhaust. Use of a turbine is not absolutely necessary: other designs include the crude pulse jet, high-speed ramjet and the still-experimental supersonic-combustion ramjet or scramjet. These designs require an existing airflow to work and cannot work when stationary, so they must be launched by a catapult or rocket booster, or dropped from a mother ship. The bypass turbofan engines of the Lockheed SR-71 were a hybrid design - the aircraft took off and landed in jet turbine configuration, and for high-speed flight the turbine was bypassed and the afterburners used to form a ramjet. The motorjet used a piston engine in place of the turbine - it was soon superseded by the turbojet and remained a curiosity.

[edit] Other forms of propulsion

- Rocket aircraft have occasionally been experimented with, and the Messerschmitt Komet fighter even saw action in the Second World War. Since then they have been restricted to rather specialised niches, such as the North American X-15 which travelled up into space where no oxygen is available for combustion (rockets carry their own oxidant). Rockets have more often been used as a supplement to the main powerplant, typically to assist takeoff of heavily-loaded aircraft, but also in a few experimental designs such as the Saunders-Roe SR.53 to provide a high-speed dash capability.

- The flapping-wing ornithopter is a category of its own. These designs may have potential, but no practical device has been created beyond research prototypes, simple toys, and a model hawk used to freeze prey into stillness so that it can be captured.

[edit] Classification by use

The major distinction in aircraft usage is between military aviation, which includes all uses of aircraft for military purposes (such as combat, patrolling, search and rescue, reconnaissance, transport, and training), and civil aviation, which includes all uses of aircraft for non-military purposes.

[edit] Military aircraft

Combat aircraft like fighters or bombers represent only a minority of the category. Many civil aircraft have been produced in separate models for military use, such as the civil Douglas DC-3 airliner, which became the military C-47/C-53/R4D transport in the U.S. military and the "Dakota" in the UK and the Commonwealth. Even the small fabric-covered two-seater Piper J3 Cub had a military version, the L-4 liaison, observation and trainer aircraft. In the past, gliders and balloons have also been used as military aircraft; for example, balloons were used for observation during the American Civil War and World War I, and cargo gliders were used during World War II to land troops.

Combat aircraft themselves, though used a handful of times for reconnaissance and surveillance during the Italo-Turkish War, did not come into widespread use until the Balkan War.

During World War I many types of aircraft were adapted for attacking the ground or enemy vehicles/ships/guns/aircraft, and the first aircraft designed as bombers were born. In order to prevent the enemy from bombing, fighter aircraft were developed to intercept and shoot down enemy aircraft. Tankers were developed after World War II to refuel other aircraft in mid-air, thus increasing their operational range. By the time of the Vietnam War, helicopters had come into widespread military use, especially for transporting, supplying, and supporting ground troops.

[edit] Civil aircraft

Civil aviation broadly divides into commercial and general activities, however in practice there is some overlap.

[edit] Commercial aircraft

Commercial aviation includes scheduled and charter airline flights. It also overlaps with a certain amount of general aviation activity where aircraft are offered for hire.

[edit] General aviation

General aviation is a catch-all covering other kinds of private and commercial use. The vast majority of flights flown around the world each day belong to the general aviation category, which covers a wide range of activities such as business trips, civilian flight training, recreation, competitive sports, firefighting, medical transport (medevac), and cargo transportation, to name a few.

Within general aviation, there is a further distinction between private flights (where the pilot is not paid for time or expenses) and commercial flights (where the pilot is paid by a client or employer). Private pilots use aircraft primarily for personal travel, business travel, or recreation. Usually they own or rent the aircraft. Commercial pilots in general aviation fly aircraft for a wide range of tasks, such as flight training, pipeline surveying, passenger and freight transport, policing, crop dusting, and medevac flights.

Piston-powered propeller aircraft (single-engine or twin-engine) are especially common for both private and commercial general aviation, but even private pilots occasionally own and operate helicopters like the Bell JetRanger or turboprops like the Beechcraft King Air. Business jets are typically flown by commercial pilots, although there is a new generation of small jets arriving soon for private pilots. Another small but important class of private aircraft are the historical warbirds.

[edit] Experimental aircraft

In layman's terms, experimental aircraft are one-off specials, built to explore some aspect of aircraft design and with no other useful purpose. The Bell X-1 rocket plane, which first broke the sound barrier in level flight, is a famous example.

The formal designation of "Experimental aircraft" also includes other types which are "not certified for commercial applications", including one-off modifications of existing aircraft such as the modified Boeing 747 which NASA uses to ferry the space shuttle from landing site to launch site, and aircraft homebuilt by amateurs for their own personal use.

[edit] Model aircraft

A model aircraft is a small unmanned type made to fly for fun, for static display, for serious aerodynamic research (cf Reynolds number) or for many other purposes. A scale model is a replica of some larger design.